The average survival rate after a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis varies depending on the type of MS, the timing and effectiveness of treatment, and individual patient factors. On average, people with MS tend to live about seven years less than the general population, but this gap has been narrowing due to advances in treatment and earlier intervention.

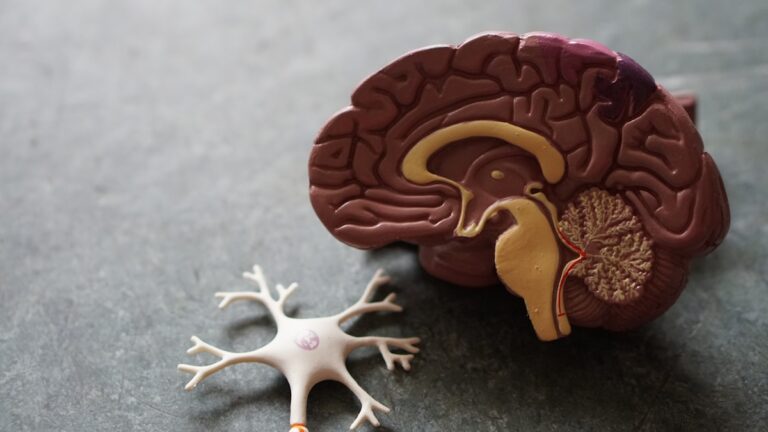

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic neurological disease that affects the central nervous system, leading to symptoms such as muscle weakness, coordination problems, and cognitive difficulties. There are different forms of MS, with the most common being relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and primary progressive MS (PPMS). RRMS is characterized by episodes of new or worsening symptoms (relapses) followed by periods of partial or full recovery (remissions). PPMS involves a steady progression of symptoms without clear relapses.

People diagnosed with RRMS generally have a better prognosis and longer survival compared to those with PPMS. Studies indicate that individuals with RRMS have an average life expectancy of about 75 years, which is roughly seven years shorter than people without MS. However, this estimate is improving as disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) become more effective and are started earlier in the disease course. Some patients with RRMS experience minimal symptoms for decades after diagnosis, especially when they receive early and optimal treatment that reduces relapses and delays disability.

PPMS, which is usually diagnosed about 10 years later than RRMS, tends to have a more gradual but steady decline in function. Life expectancy in PPMS may be somewhat shorter than in RRMS, and women with PPMS often have a shorter lifespan than men with the same condition. Despite the progressive nature of PPMS, it is not considered a fatal disease by itself; most people with PPMS die from common causes such as heart disease or cancer rather than MS directly. Nevertheless, the progressive disability associated with PPMS can lead to complications that affect survival.

The introduction and widespread use of disease-modifying therapies have significantly influenced survival rates in MS. These treatments, including interferons, glatiramer acetate, and newer agents like natalizumab and ublituximab, help reduce the frequency and severity of relapses and may slow disease progression. Early and sustained treatment is associated with better long-term outcomes and improved survival. Over half of older adults with MS are now prescribed DMTs, reflecting the growing emphasis on managing MS as a chronic condition.

Despite these advances, MS still contributes to an increased risk of mortality compared to the general population. Research shows that patients with MS have higher mortality rates, largely due to complications such as infections, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary problems. In particular, late-stage MS can impair swallowing, coughing, and breathing, increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia and respiratory failure. Managing these complications effectively can have a significant impact on survival.

In summary, while MS reduces average life expectancy by several years, the outlook has improved considerably with modern treatments and better symptom management. Survival varies by MS type, with relapsing-remitting forms generally associated with longer life than progressive forms. Ongoing research and new therapies continue to enhance quality of life and extend survival for people living with MS.