Smoking increases a person’s annual radiation dose far more significantly than living at high altitude. While both smoking and high-altitude living expose individuals to increased levels of radiation, the magnitude and health impact of radiation from smoking are substantially greater.

To understand this, it helps to look at the sources and types of radiation involved. High-altitude environments expose people to increased cosmic radiation because the atmosphere is thinner and offers less shielding from high-energy particles originating from space. This cosmic radiation dose increases with altitude, roughly doubling every 1,500 to 2,000 meters above sea level. For example, people living at altitudes around 3,000 meters receive an additional dose of a few millisieverts (mSv) per year compared to sea level. This increase is relatively modest and generally considered a low-level chronic exposure.

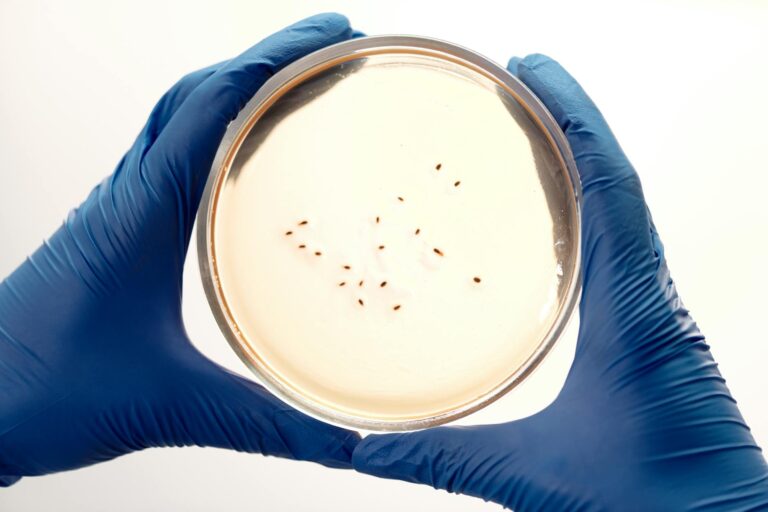

In contrast, smoking introduces radioactive substances directly into the lungs. Tobacco plants naturally absorb radioactive isotopes such as polonium-210 and lead-210 from the soil and fertilizers. When tobacco is burned and inhaled, these radioactive particles lodge deep in lung tissue, delivering localized alpha radiation doses that are far more intense than the diffuse cosmic radiation at high altitudes. This internal radiation exposure from smoking is cumulative and concentrated, contributing significantly to lung tissue damage and cancer risk.

Quantitatively, the annual effective radiation dose from living at high altitude might increase by a few millisieverts at most. Meanwhile, smoking a pack of cigarettes per day can deliver an estimated radiation dose to the lungs equivalent to several hundred millisieverts per year, depending on smoking intensity and duration. This is orders of magnitude higher than the dose increase from altitude.

The health consequences reflect this difference. High-altitude radiation exposure is generally low enough that it does not cause a measurable increase in cancer risk for most residents, although some adaptive biological responses to chronic low-dose radiation have been observed. On the other hand, smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer worldwide, responsible for 80-90% of cases. The radioactive particles in tobacco smoke contribute to DNA damage and mutations in lung cells, compounding the harmful effects of chemical carcinogens in smoke.

In addition to radiation, smoking delivers numerous toxic chemicals that further increase cancer risk and other diseases, making its overall health impact far more severe than the relatively mild radiation increase from high-altitude living.

In summary, while both smoking and high-altitude living increase radiation exposure, the **internal radiation dose from smoking is vastly higher and far more dangerous** than the external cosmic radiation dose increase experienced at high altitudes. This explains why smoking is a major health hazard with a strong link to lung cancer, whereas high-altitude living poses only a minor radiation risk.