Smoking and Fukushima background radiation are fundamentally different in nature, sources, and health impacts, so equating smoking to Fukushima background radiation is misleading and scientifically inaccurate.

Smoking involves inhaling tobacco smoke, which contains thousands of chemicals, including nicotine, tar, carbon monoxide, and about 70 known carcinogens. These substances directly damage the lungs, heart, and blood vessels, increasing the risk of diseases such as lung cancer, coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Smoking accelerates arterial deterioration, causes blood clotting abnormalities, and leads to oxygen deprivation in vital organs. It also harms non-smokers through secondhand and thirdhand smoke exposure, which contain toxic chemicals that linger in the environment and increase lung cancer risk even in those who never smoke themselves. The health risks from smoking are immediate and cumulative, with long-term smokers facing significantly higher chances of fatal diseases[1][2][3].

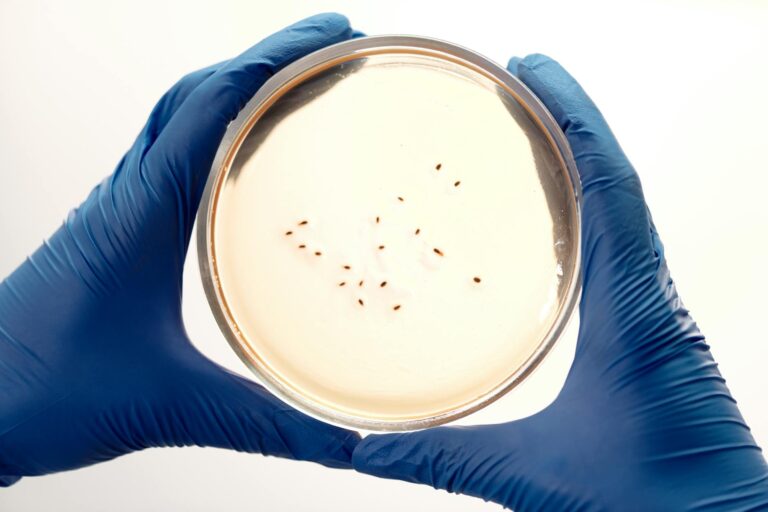

Fukushima background radiation, on the other hand, refers to the low-level radioactive contamination released into the environment following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. This radiation consists mainly of ionizing radiation from radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137 and iodine-131. Ionizing radiation can damage DNA and cells, potentially increasing cancer risk, but the levels of radiation exposure to the general population from Fukushima have been monitored and found to be low and within safety limits. Unlike smoking, which introduces chemical toxins directly into the body, background radiation exposure is external and typically at much lower doses. The health effects of low-dose radiation exposure are complex and depend on dose, duration, and individual susceptibility. While high doses of radiation are clearly harmful, the risk from low-level background radiation remains a subject of scientific study and debate, with no direct equivalence to the acute and chronic chemical toxicity of smoking[4].

A common comparison sometimes made is that living in a highly polluted environment or being exposed to certain environmental hazards can be “like smoking X cigarettes a day” to illustrate relative risk. For example, air pollution in some cities has been compared to smoking 10–15 cigarettes daily in terms of lung cancer risk. However, this analogy is about chemical pollution, not radiation. Fukushima background radiation levels are far lower than the radiation doses known to cause immediate health effects and are not comparable to the direct chemical assault caused by smoking tobacco[5].

In summary, smoking delivers a potent cocktail of harmful chemicals directly into the lungs and bloodstream, causing well-documented and severe health consequences. Fukushima background radiation involves low-level ionizing radiation exposure from environmental contamination, with health risks that are generally much lower and less direct. The two are not equivalent in exposure type, intensity, or health impact, so saying smoking equals Fukushima background radiation is an oversimplification that ignores the distinct nature of chemical versus radiological hazards.