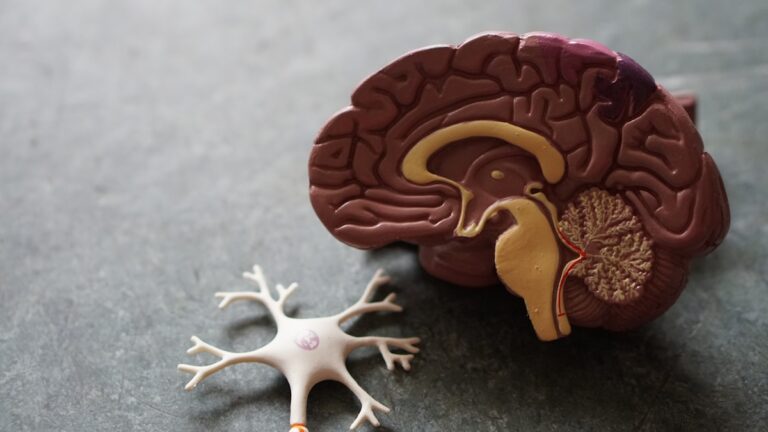

Homocystinuria is caused primarily by genetic mutations that disrupt the normal metabolism of the amino acid methionine, leading to an accumulation of homocysteine and related compounds in the body. The most common cause is a mutation in the gene that produces the enzyme cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS). This enzyme is crucial for converting homocysteine into cystathionine, which is then further processed into other important molecules. When CBS is deficient or malfunctioning due to these mutations, homocysteine builds up in the blood and urine, causing toxic effects.

More than 150 different mutations in the CBS gene have been identified, each altering the enzyme’s structure or function. One frequent mutation involves the substitution of the amino acid isoleucine with threonine at position 278 of the enzyme, known as Ile278Thr. These mutations impair the enzyme’s ability to catalyze the conversion of homocysteine, leading to its accumulation. In some cases, the CBS enzyme may be overactive (upregulated), causing abnormal chemical reactions that also disrupt normal metabolism.

Homocystinuria is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning a person must inherit defective copies of the CBS gene from both parents to develop the disorder. If only one defective gene is inherited, the person is typically a carrier without symptoms. Because of this inheritance pattern, the disorder often appears in families with consanguineous marriages, where parents are related by blood, increasing the chance of both passing on the mutated gene.

The buildup of homocysteine damages various tissues and organs. It can cause connective tissue abnormalities that resemble Marfan syndrome, such as long limbs and fingers, but also leads to additional problems like osteoporosis (weak bones), mental deterioration, and a tendency for blood clots (thrombosis). The elevated homocysteine levels damage blood vessel walls, increasing the risk of vascular diseases including atherosclerosis and blood clots in coronary and peripheral vessels. This vascular damage can be severe enough to cause life-threatening complications even in childhood.

Besides CBS mutations, other genetic factors can influence homocysteine metabolism. For example, mutations in the MTHFR gene, which affects folate metabolism, can also raise homocysteine levels, though these mutations typically cause milder forms of hyperhomocysteinemia rather than classic homocystinuria.

In summary, homocystinuria results from inherited defects in enzymes responsible for processing methionine and homocysteine, most notably cystathionine beta-synthase. These genetic mutations disrupt normal amino acid metabolism, leading to toxic accumulation of homocysteine, which causes a range of connective tissue, neurological, and vascular problems. The disorder’s autosomal recessive inheritance means it appears when both parents pass on defective genes, often seen in families with close genetic relationships.