Vitiligo is a skin condition where patches of skin lose their natural color, turning white due to the destruction or malfunction of melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin, the pigment that gives skin its color. The exact cause of vitiligo is not fully understood, but it is widely accepted to be a complex condition influenced by multiple factors, including autoimmune responses, genetics, environmental triggers, and oxidative stress.

The most prominent theory explaining vitiligo is the **autoimmune hypothesis**. In this scenario, the body’s immune system mistakenly identifies melanocytes as harmful and attacks them, leading to their destruction. This immune attack results in the loss of pigment in affected areas. This autoimmune activity is supported by the fact that vitiligo often occurs alongside other autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disorders, type 1 diabetes, and alopecia areata, suggesting a systemic immune dysregulation.

Genetics also play a significant role in vitiligo. Many people with vitiligo have a family history of the condition or other autoimmune diseases, indicating a hereditary predisposition. Researchers have identified several genes associated with immune regulation and melanocyte function that may increase susceptibility to vitiligo. However, having these genes does not guarantee the development of vitiligo, implying that environmental factors are also crucial.

Environmental triggers can include physical trauma to the skin (such as cuts, sunburn, or friction), exposure to certain chemicals, and emotional or physical stress. These triggers may initiate or exacerbate the immune response against melanocytes. For example, sunburn can damage melanocytes directly and may also provoke an immune reaction that worsens vitiligo. Similarly, exposure to industrial chemicals like phenols and catechols has been linked to melanocyte damage.

Another important factor is **oxidative stress**, which refers to an imbalance between free radicals (unstable molecules that can damage cells) and antioxidants (molecules that neutralize free radicals). In people with vitiligo, melanocytes may be more vulnerable to oxidative damage, leading to their dysfunction or death. This oxidative stress might also stimulate the immune system to attack melanocytes.

There are also neurogenic theories suggesting that nerve-related chemicals released in the skin might harm melanocytes or trigger immune responses. This could explain why vitiligo sometimes follows nerve distributions or appears after nerve injury.

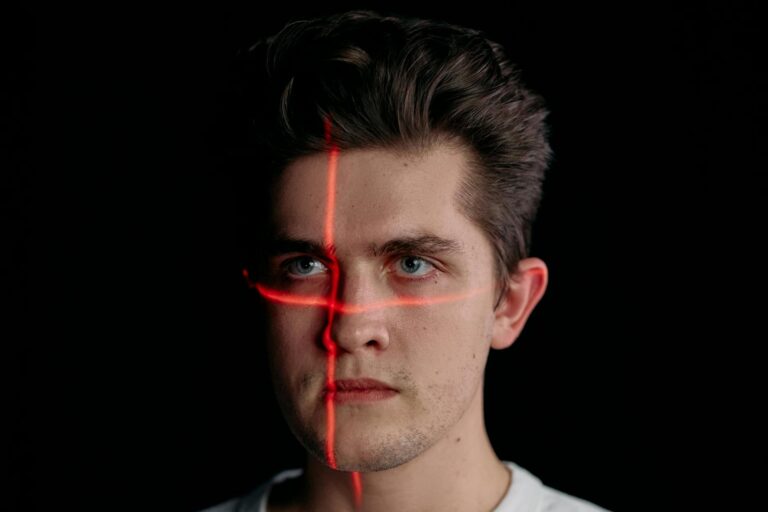

Clinically, vitiligo manifests as sharply defined white patches that often begin on areas exposed to the environment, such as the face, hands, feet, and around body openings like the mouth and eyes. The pattern of these patches can vary: some people have symmetrical patches on both sides of the body, while others have segmental vitiligo, where patches appear on one side or in a localized area. In severe cases, vitiligo can spread extensively, affecting large portions of the skin and even hair, causing premature whitening.

Vitiligo affects people of all skin types and ethnicities, but the contrast between the white patches and normal skin is more noticeable in individuals with darker skin, which can lead to social and psychological challenges. The condition often begins before the age of thirty, with many cases appearing in childhood or adolescence.

In summary, vitiligo is caused by a combination of autoimmune destruction of melanocytes, genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and oxidative stress. These factors interact in complex ways to cause the loss of skin pigment in affected individuals. The exact interplay and relative importance of each factor can vary from person to person, making vitiligo a multifactorial and still somewhat mysterious condition.