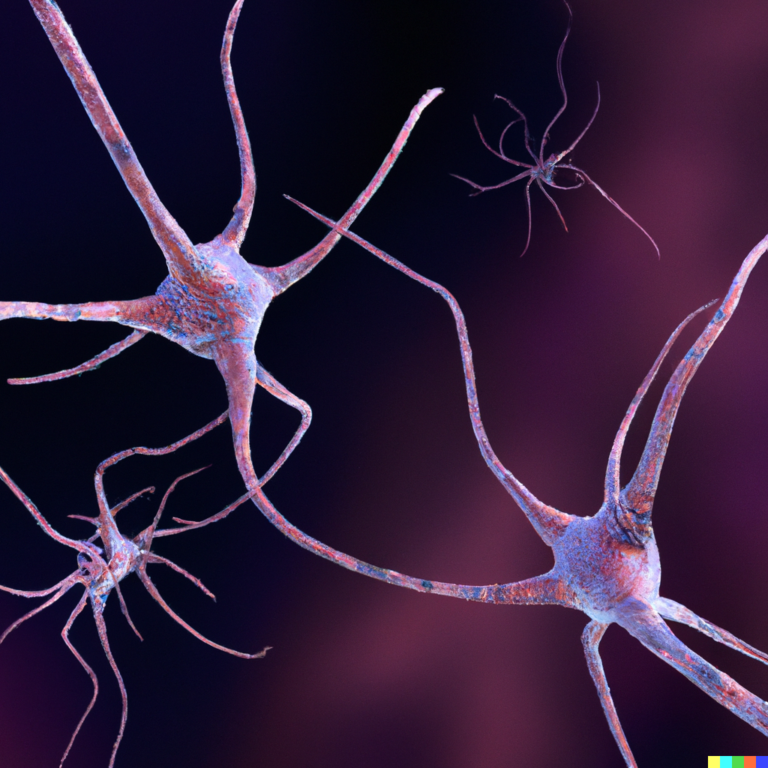

MRI scans can measure brain atrophy in Parkinson’s disease, but the process is complex and requires advanced imaging techniques and analysis methods to detect subtle changes. Brain atrophy refers to the loss of neurons and the connections between them, leading to shrinkage of brain tissue. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), this atrophy tends to occur gradually and affects specific brain regions involved in motor control, cognition, and other functions.

Standard MRI scans typically do not show clear signs of Parkinson’s disease because PD primarily involves microscopic changes such as loss of dopamine-producing neurons rather than large-scale structural damage visible on routine imaging. However, specialized MRI approaches can quantify brain volume changes over time or compare volumes between patients with PD and healthy controls to identify patterns of atrophy.

The most commonly affected areas where MRI detects atrophy in PD include parts of the basal ganglia (such as the substantia nigra), cerebral cortex regions like the temporal lobe, and subcortical structures including the thalamus. Temporal lobe atrophy has been observed especially in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia, distinguishing it from other dementias like Alzheimer’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Longitudinal MRI studies—those that scan patients repeatedly over months or years—are particularly valuable for measuring progression of brain atrophy in PD. These studies reveal that brain shrinkage tends to ascend through different regions as severity increases. Advanced computational methods such as machine learning algorithms applied to whole-brain MRI data help differentiate PD from related disorders like multiple system atrophy by identifying distinct patterns of regional volume loss.

Brain volume measurements using synthetic MRI techniques have also been used recently to classify subtypes within Parkinson’s disease based on their unique trajectories of brain tissue loss. This helps link clinical symptoms with underlying neurodegeneration more precisely.

Despite these advances, there are challenges:

– The rate of progression varies widely among individuals.

– Atrophic changes may be subtle early on.

– Co-existing pathologies can complicate interpretation.

– Clinical symptoms do not always correlate directly with measured structural decline.

Therefore, researchers advocate for adaptable models integrating multimodal imaging data along with clinical assessments and genetic information for better prediction and monitoring.

In summary, while standard MRIs alone cannot diagnose Parkinson’s or fully capture its complexity, modern neuroimaging techniques enable measurement of brain atrophy associated with PD by focusing on specific vulnerable regions over time using sophisticated analysis tools. This provides important insights into disease progression that support both research efforts and potentially future clinical management strategies aimed at tracking neurodegeneration more accurately.