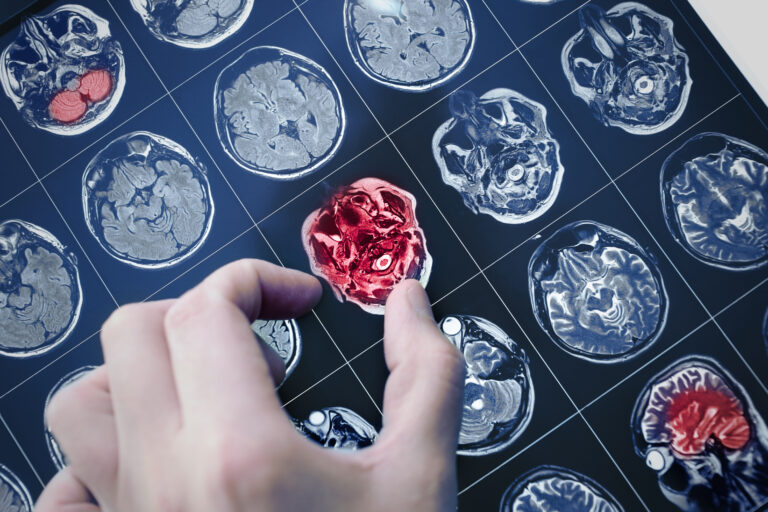

Radiation affects rapidly dividing cells more strongly because these cells are more vulnerable to damage during the process of cell division, particularly when their DNA is being copied and prepared for splitting into new cells. Radiation primarily harms cells by causing breaks in their DNA strands. When a cell is dividing, its DNA is unwound and duplicated, making it more exposed and susceptible to damage. If the DNA damage is severe or improperly repaired, the cell cannot divide correctly and may die or become dysfunctional.

Rapidly dividing cells, such as those in the bone marrow, skin, and lining of the gastrointestinal tract, are constantly replicating their DNA and dividing to replace old or damaged cells. This high turnover rate means there are more cells in vulnerable phases of the cell cycle at any given time, increasing the likelihood that radiation will disrupt their DNA during these critical moments. In contrast, cells that divide slowly or are in a resting phase are less likely to be caught in this sensitive state and thus are less affected by radiation.

Moreover, rapidly dividing cells often have less efficient DNA repair mechanisms compared to normal, slower-dividing cells. Cancer cells, for example, tend to have impaired DNA repair pathways, making them particularly sensitive to radiation-induced DNA damage. When radiation causes double-strand breaks in DNA, these cells struggle to fix the damage, leading to a phenomenon called mitotic catastrophe, where the cell fails to complete division and dies.

The destruction of progenitor or stem cells in rapidly renewing tissues leads to early radiation effects because these cells are essential for maintaining tissue structure and function. When these progenitor cells are killed, the tissue cannot replenish itself, resulting in symptoms like skin irritation, mucosal inflammation, or bone marrow suppression.

In addition to DNA damage, radiation can induce oxidative stress and generate free radicals that further harm cellular components. Rapidly dividing cells, due to their metabolic activity and replication demands, are less able to cope with this oxidative damage.

Newer radiation techniques, such as FLASH radiotherapy, aim to exploit these differences by delivering radiation at ultra-high dose rates that preferentially kill tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. This selective effect may be related to differences in iron metabolism and oxygen availability between cancerous and healthy cells, but the precise mechanisms are still under investigation.

In summary, the heightened sensitivity of rapidly dividing cells to radiation stems from their frequent DNA replication, vulnerability during cell division, less effective DNA repair, and critical role in tissue renewal, all of which make them prime targets for radiation-induced damage.