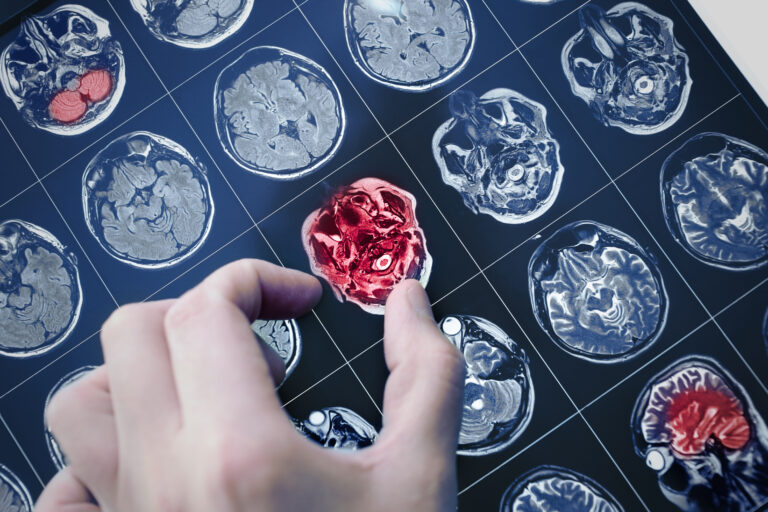

Targeted radiation can be more effective than surgery in certain cancer treatments, but the answer depends heavily on the type of cancer, its stage, location, and patient-specific factors. Both targeted radiation and surgery have distinct advantages and limitations, and their effectiveness varies based on the clinical context.

Targeted radiation therapy, such as intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) or advanced external beam radiation techniques, aims to precisely deliver high doses of radiation directly to the tumor while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. This precision reduces side effects and preserves organ function. For example, in early-stage breast cancer, studies have shown that IORT can provide a favorable short-term prognosis compared to postoperative radiotherapy, with similar long-term outcomes. This suggests that targeted radiation can be an effective alternative to surgery or a complement to it, especially when combined with breast-conserving surgery[1].

Radiation therapy is non-invasive, meaning it does not require incisions or physical removal of tissue. This results in no blood loss, lower risk of surgical site infections, and generally faster recovery times compared to surgery. Patients undergoing radiation often avoid hospitalization and can receive treatment on an outpatient basis. Modern radiation techniques use real-time imaging, dose modulation, and AI automation to maximize tumor targeting and minimize damage to nearby organs, which improves quality of life by preserving functions such as voice in throat cancer patients[4].

On the other hand, surgery physically removes the tumor and sometimes surrounding tissue, which can be definitive in eliminating localized cancer. Surgery is often preferred when the tumor is accessible and when complete removal is feasible without excessive harm to the patient. For certain cancers, such as prostate cancer with oligometastatic spread, surgery has shown promising survival benefits compared to radiotherapy alone, with acceptable complication rates. However, surgery carries risks such as infection, longer recovery, pain, and potential functional impairments depending on the extent of tissue removal[5].

In some cancers, a combined approach is used. For example, minimally invasive surgery followed by a shorter, less intense course of radiation and chemotherapy has been shown to reduce side effects while maintaining high cure rates in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. This approach balances the benefits of tumor removal with the precision and organ preservation of targeted radiation[2][3].

Effectiveness also depends on tumor biology. For hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients under 50, radiotherapy may not significantly impact prognosis, indicating that surgery or other systemic treatments might be more critical in such cases[1]. Similarly, high-risk patients with extensive lymph node involvement may benefit more from standard, intensive treatments rather than de-escalated radiation regimens[2].

In summary, targeted radiation is often more effective than surgery when the goal is to preserve organ function, reduce treatment-related morbidity, and when the tumor is sensitive to radiation. Surgery may be more effective for complete tumor removal in accessible cancers or when immediate physical removal is necessary. The choice between targeted radiation and surgery is highly individualized, often involving multidisciplinary evaluation to optimize outcomes based on tumor characteristics, patient health, and treatment goals.