Alcohol consumption is not safe for people with Alzheimer’s disease or those at risk of developing it. Recent authoritative research shows that **any amount of alcohol increases the risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease**, and there is no safe or protective level of drinking for brain health in this context[1][2][3].

A large study published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine in 2025 analyzed data from over 559,000 adults aged 56 to 72 in the United States and Britain. The study combined observational data with genetic analyses to understand the relationship between alcohol use and dementia risk. It found that even light drinking—defined as fewer than six drinks per week—was associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. The risk rose steadily with higher alcohol consumption, and heavy drinking (more than 40 drinks per week) posed the greatest risk[1].

This study challenges earlier beliefs that moderate alcohol consumption might protect the brain. The genetic analysis was crucial because it helped rule out confounding factors and reverse causation. Reverse causation means that people who are developing dementia might reduce their drinking before diagnosis, which could have led previous studies to mistakenly conclude that moderate drinking was protective. Instead, the genetic data showed a clear causal link: **greater alcohol consumption leads to higher dementia risk** regardless of genetic predisposition[3].

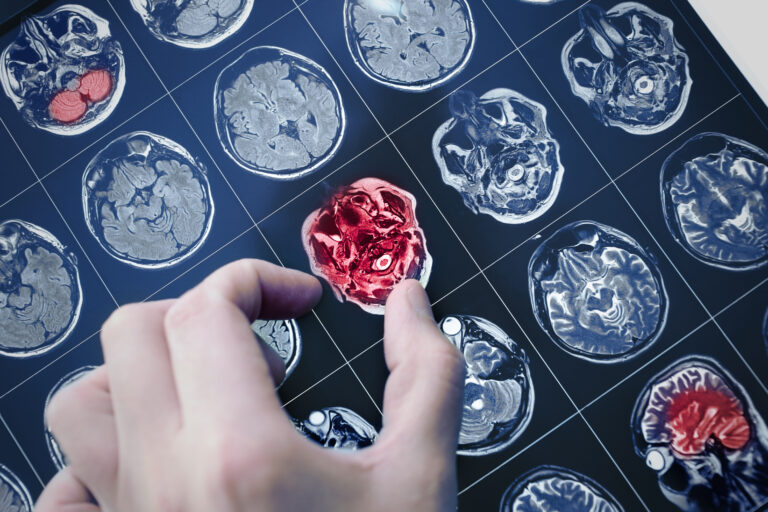

Alcohol harms the brain through several mechanisms. It is neurotoxic, meaning it damages neurons directly. It promotes brain atrophy (shrinkage), disrupts neurotransmitter systems that are essential for communication between brain cells, and accelerates vascular injury, which affects blood flow to the brain. Chronic alcohol use can impair thiamine metabolism, leading to cognitive deficits. Even low levels of alcohol consumption have been linked to reduced gray matter volume in brain imaging studies. Alcohol also increases systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which contribute to neurodegeneration—the progressive loss of structure or function of neurons seen in Alzheimer’s disease[2].

For people who already have Alzheimer’s disease, alcohol can worsen symptoms and accelerate cognitive decline. Since Alzheimer’s involves progressive brain damage, adding alcohol’s neurotoxic effects can compound the problem. Alcohol may also interfere with medications used to manage Alzheimer’s symptoms and increase the risk of falls, injuries, and other complications common in dementia patients.

Public health experts now emphasize that **reducing or eliminating alcohol consumption is an important strategy for dementia prevention**. This advice applies not only to those with Alzheimer’s but also to older adults in general, as alcohol increases the risk of developing dementia in the first place[1][3][4].

In summary, the current scientific consensus based on large-scale, rigorous studies is that alcohol is harmful to brain health and increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. There is no safe level of alcohol consumption for people with Alzheimer’s or those at risk of it. Avoiding alcohol is the safest choice to protect brain function and slow cognitive decline.

Sources:

[1] Anya Topiwalal, Daniel F. Levey, Hang Zhou, et al. “Alcohol use and risk of dementia in diverse populations: evidence from cohort, case–control and Mendelian randomisation approaches.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, September 23, 2025.

[2] Medical News Today. “Even small amounts of alcohol may increase dementia risk, study finds.” October 2025.

[3] Psychiatrist.com. “Even Moderate Alcohol Consumption Drives Up Dementia Risk.” September 2025.

[4] News-Medical.net. “Drinking any amount of alcohol may raise dementia risk.” September 2025.