Eating a sardine loaf does not equal the radiation dose received from a chest X-ray. These two are fundamentally different in nature: one involves ingesting food, while the other involves exposure to ionizing radiation used in medical imaging.

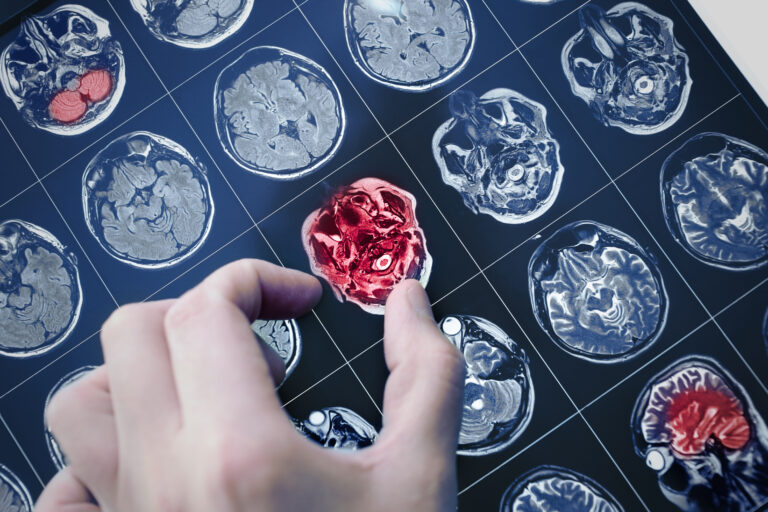

A chest X-ray is a diagnostic tool that uses a small amount of ionizing radiation to create images of the chest, including the lungs, heart, and bones. The radiation dose from a typical chest X-ray is very low but measurable, usually around 0.1 millisieverts (mSv). This dose is enough to penetrate tissues and produce an image but is considered safe for most people when used appropriately.

On the other hand, eating a sardine loaf involves consuming food that contains nutrients, fats, proteins, and possibly trace amounts of naturally occurring radioactive elements like potassium-40 or radium, which are present in many foods at very low levels. However, the radiation dose from these natural sources in food is minuscule compared to medical imaging. The radiation you get from eating even a large amount of sardines or any other food is negligible and does not compare to the controlled exposure from an X-ray.

To put it simply, the radiation exposure from a chest X-ray is a brief, external exposure to ionizing radiation designed to pass through the body to create an image. The radiation from food is internal but comes from very low levels of naturally occurring radioactive isotopes, which are part of the background radiation we are all exposed to daily. The dose from food is typically thousands of times lower than that from a single chest X-ray.

Therefore, eating sardine loaf does not equal the radiation dose of a chest X-ray. The two are not comparable in terms of radiation exposure or health impact. The X-ray dose is a specific, controlled medical exposure, while the radiation from food is a tiny, natural background level that poses no significant risk.