The question of whether eating sardine fritters equals the radiation exposure from a mammogram is an interesting one that touches on how we understand radiation in everyday life versus medical procedures. To unpack this, it’s important to first clarify what kind of radiation we’re talking about in each case, and how they compare in terms of exposure and risk.

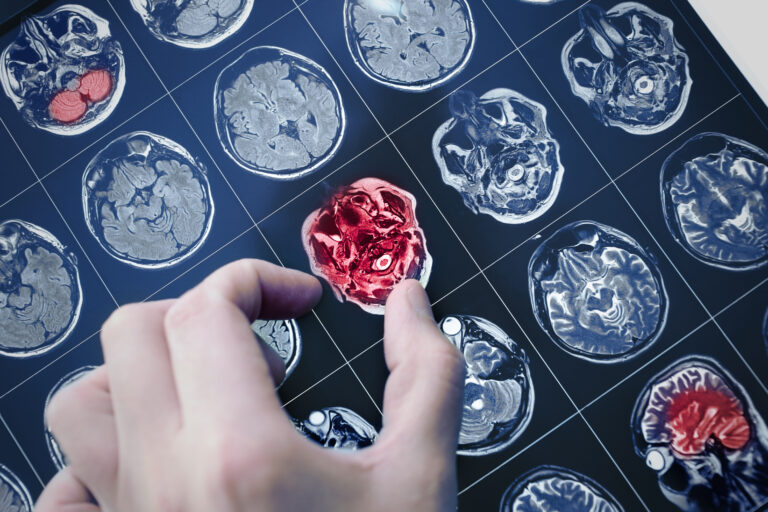

Mammograms are a type of medical imaging that uses low-dose X-rays to look at breast tissue. The radiation involved here is ionizing radiation, which means it has enough energy to remove tightly bound electrons from atoms, potentially causing damage to DNA and cells. This is why mammograms are carefully regulated and recommended only at certain intervals, balancing the benefits of early cancer detection against the small risks from radiation exposure.

On the other hand, sardine fritters, or any food for that matter, do not emit ionizing radiation. However, some foods naturally contain trace amounts of radioactive elements like potassium-40 or carbon-14, which are naturally occurring isotopes present in the environment and in all living things. These isotopes emit very low levels of radiation, but this is a normal part of the natural background radiation we are exposed to every day. Eating sardines, which are fish, means you ingest tiny amounts of these naturally radioactive isotopes, but the level is extremely low and not harmful.

When people say eating sardine fritters equals mammogram radiation, they are usually referring to the concept of *radiation dose equivalence*—trying to compare the tiny natural radiation dose from food to the controlled dose from a mammogram. But this comparison can be misleading because the types of radiation and their biological effects differ significantly.

A mammogram delivers a specific, measurable dose of ionizing radiation targeted at breast tissue, designed to produce detailed images. This dose is small but deliberate and controlled. The radiation from naturally radioactive isotopes in food is diffuse, very low in intensity, and spread throughout the body once ingested. It’s part of the background radiation we all receive from the environment, including cosmic rays, soil, and even the air we breathe.

To put it simply, the radiation dose from a mammogram is much higher than the radiation dose you get from eating sardine fritters. The natural radioactivity in food is so low that it’s generally considered negligible in terms of health risk. In fact, the radiation from a single mammogram is roughly equivalent to a few months of natural background radiation exposure, which includes what you get from food, air, and the ground.

Another important point is that the body has evolved mechanisms to repair the small amounts of DNA damage caused by everyday background radiation. The radiation from food is part of this background and does not accumulate in a harmful way. Mammogram radiation, while higher, is still low enough that the benefits of detecting breast cancer early outweigh the risks for most women.

It’s also worth noting that the idea of comparing food radiation to medical radiation can sometimes cause unnecessary fear or confusion. Radiation in medicine is carefully controlled and justified by its benefits. Natural radiation in food is unavoidable and harmless at the levels we consume.

In summary, eating sardine fritters does not equal the radiation from a mammogram. The radiation from food is natural, very low, and spread throughout the body, while mammogram radiation is a controlled, targeted dose designed for diagnostic purposes. Understanding these differences helps put radiation exposure into perspective and reduces misconceptions about everyday radiation sources.