Radioactive isotopes do not generally accumulate permanently in the body; instead, their presence and effects depend on the specific isotope’s chemical behavior, biological processing, and radioactive decay characteristics. When radioactive isotopes enter the body, they may initially concentrate in certain organs or tissues based on their chemical similarity to naturally occurring elements, but over time, most are eliminated through biological processes or decay into stable or less harmful forms.

For example, iodine-131, a radioactive isotope commonly encountered in medical treatments and nuclear fallout, accumulates primarily in the thyroid gland because the thyroid naturally absorbs iodine. However, iodine-131 has a relatively short half-life (about 8 days) and is gradually eliminated from the body through urine, sweat, and natural radioactive decay within a few weeks. This means it does not remain permanently but poses a temporary radiation risk while present. Patients treated with iodine-131 are advised to take precautions to avoid exposing others during this period, but the isotope itself does not stay indefinitely in the body[1][4].

Similarly, technetium-99m, widely used in medical imaging, is chosen because it emits gamma rays useful for diagnostics but has a very short half-life of about 6 hours and is cleared from the body quickly, usually within a day. Its decay product, technetium-99, has a very long half-life but emits very little radiation and is chemically different, so it does not accumulate in the same way or cause significant harm[3].

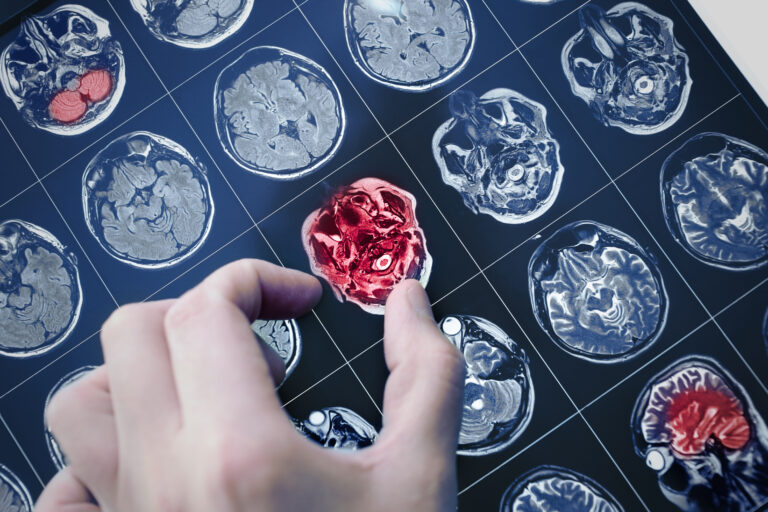

Some alpha-emitting isotopes used in targeted cancer therapies, such as actinium-225 and its decay products, can redistribute within the body after administration. Research shows that daughter isotopes produced by decay can move to different organs, such as kidneys, liver, or intestines, due to nuclear recoil effects and biological transport. This redistribution can cause side effects but still does not mean permanent accumulation; rather, these isotopes continue to decay and are eventually eliminated or rendered harmless[5].

In general, the human body has mechanisms to excrete many radioactive isotopes through urine, feces, sweat, and other routes. The rate of elimination depends on the isotope’s chemical form and biological half-life (how long it stays in the body before being excreted). Radioactive decay also reduces the amount of radioactive material over time. Therefore, while radioactive isotopes can temporarily accumulate in specific tissues, they do not remain permanently in the body.

However, some radioactive elements with very long half-lives and chemical properties similar to essential minerals (like radium or plutonium) can deposit in bones or organs and remain for years, posing long-term radiation risks. These cases are exceptions rather than the rule and usually involve exposure to high levels of radioactive contamination rather than typical medical or environmental exposure.

In summary, radioactive isotopes introduced into the body tend to accumulate temporarily in certain tissues based on their chemistry but are generally eliminated biologically or decay radioactively over time. Permanent accumulation is rare and depends on the isotope’s nature, exposure level, and biological behavior.